Integrating elements of the natural world into interior and architectural design has become big news. Effect Magazine’s Dominic Lutyens speaks to the movement’s proponents to discover why.

The psychologist Erich Fromm first used the term biophilia in 1973 to describe “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive”. Dormant for some time, it’s now resurfacing, and is being widely championed by interior designers and architects, more specifically as biophilic design.

Biophilia is now commonly understood to mean human beings’ innate desire to connect with nature. A catchy buzzword bandied around in the design community today, it’s nevertheless regarded as relevant to our growing concern with the environment.

Biophilia’s close relationship to biodiversity also explains why it’s taken seriously. The addition of greenery in overlooked, urban spaces is one of the most environmentally effective applications of biophilic design – and when introduced to spaces such as disused industrial sites or car parks, it helps to combat air pollution and ‘urban heat-island effect’ (urban areas that are warmer than surroundings rural areas due to human activities).

Obvious signs of biophilic design in modern cities are the vertical gardens that urban architecture increasingly incorporates. The first large indoor green wall was constructed in Paris’ La Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie in in 1986, and the number of vertical gardens has in recent times surged dramatically.

Biophilic elements mimic nature’s ability to surprise in the form of dramatic effects.

Debbie Flevotomou, architect

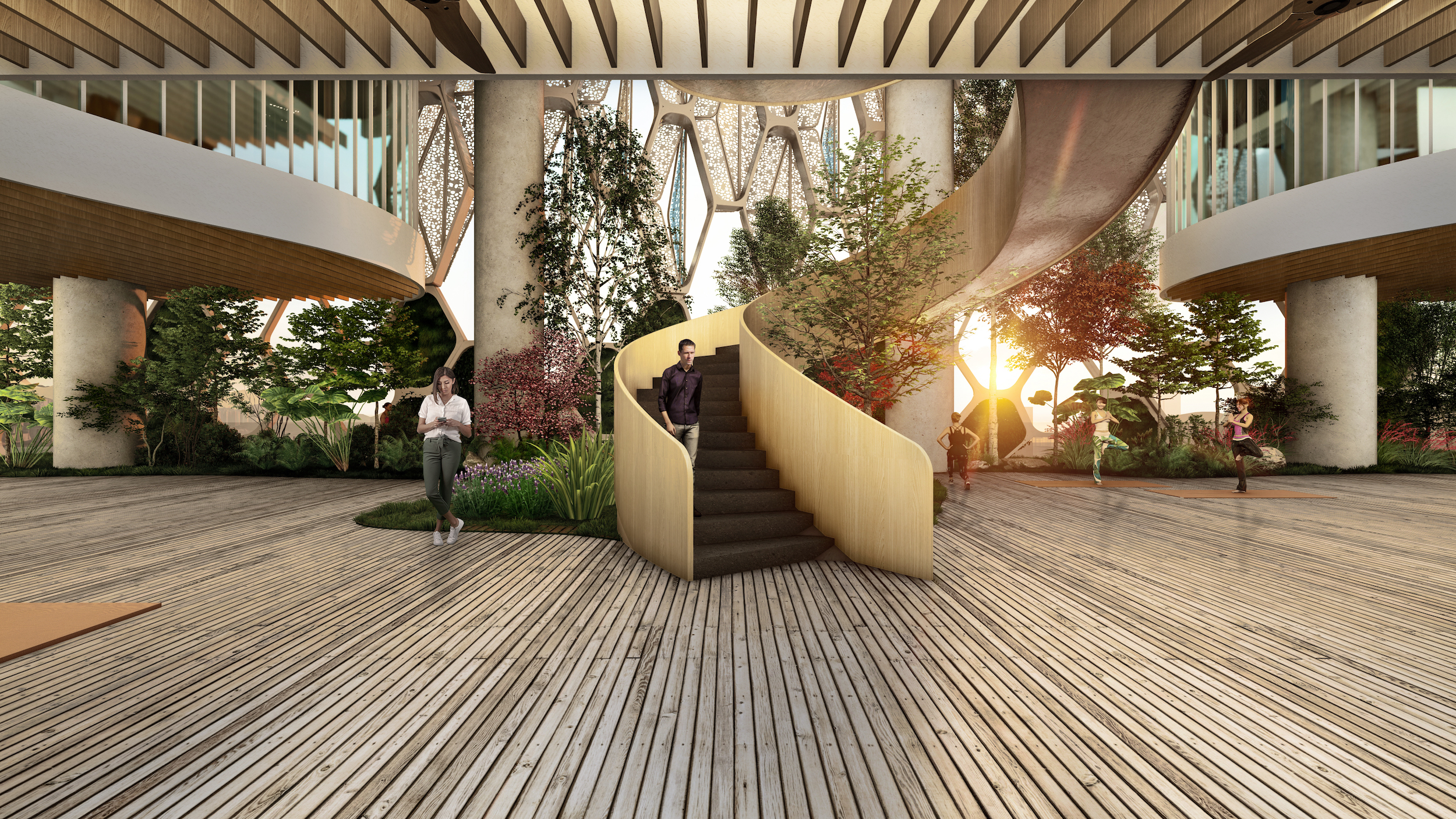

Biophilic design has also become a global phenomenon. It can be found at arts centre Sfer Ik (top and below), part of the 100-acre complex AZULIK Uh May in Mexico. Located in the jungle and following biophilic principles, Sfer Ik incorporates locally sourced, sustainable materials such as the vine-like wood bejuco. “Artists here can create an atmosphere unlike any other art space today,” says Marcello Dantas, the museum’s director. “In a world that desperately needs more sustainable practices this is an opportunity to develop them.”

The museum will host an exhibition from March to September by Japanese artist Azuma Makoto, who will create a site-specific installation made of living, indigenous flowers which will grow into the gallery space.

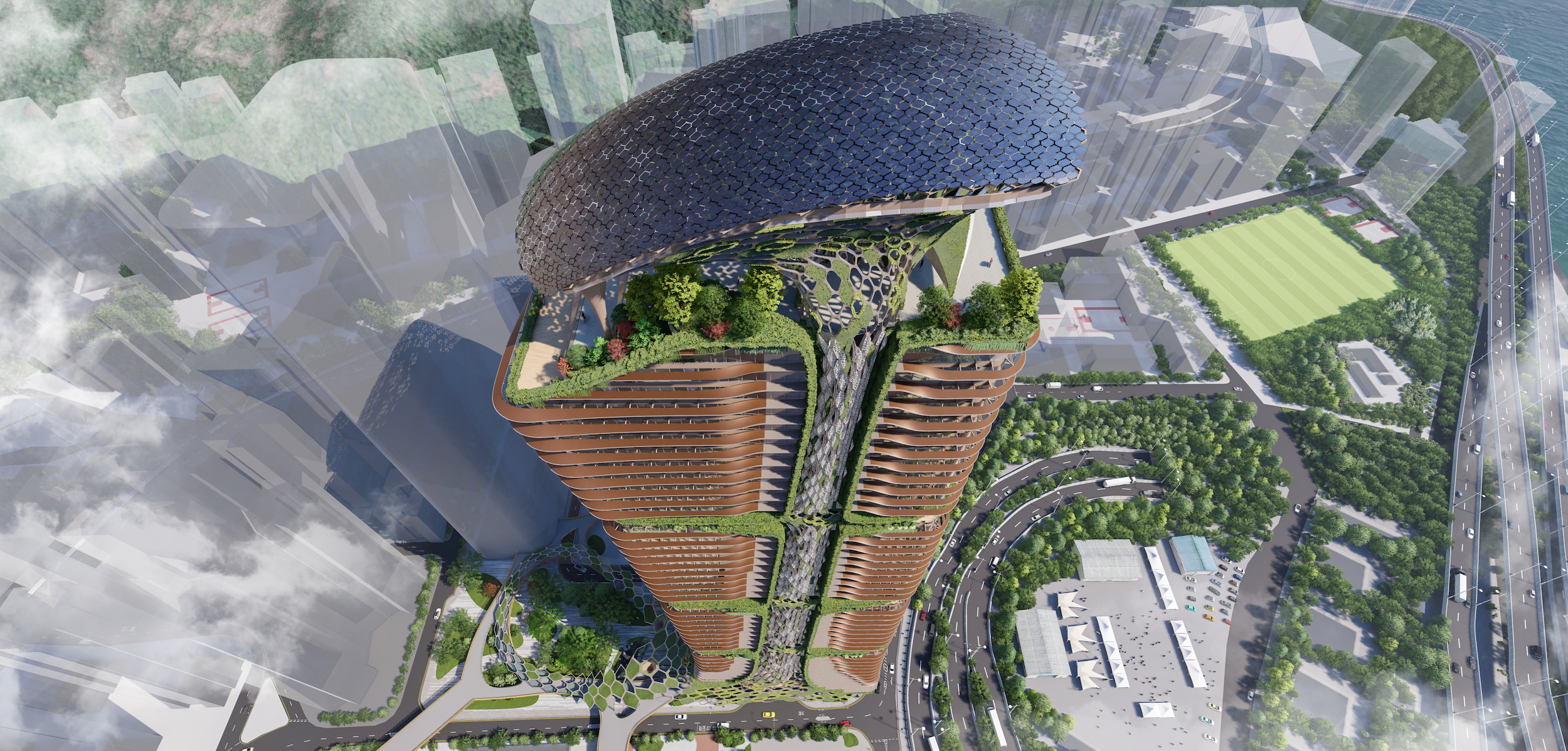

Biophilic design has also been adopted by Hong Kong-based Ronald Lu & Partners, which has won an international Advancing Net Zero Ideas competition in the Future Building category for a new high-rise office concept, The Treehouse, which would feature internal and external green walls and roofs, and water features. According to MK Leung, the practice’s Director of Sustainable Design: “Biophilic design brings landscaping into and onto buildings, roads and structures to embed nature into the built environment.”

Biophilic design brings landscaping into and onto buildings, roads and structures to embed nature into the built environment.

MK Leung, Director of Sustainable Design, Ronald Lu & Partners

Leung cites Singapore as having pioneered biophilia in Southeast Asia, a region that recorded the highest number of threatened species in 2014, according to the United Nations Environment Programme: “Singapore’s objective to become a ‘City in a Garden’ has meant the creation of natural spaces to accommodate its five million residents by blending architecture and biophilia. A Green Building code has been mandatory since 2008 and it’s normal to find plants on roofs and facades and inside buildings, too.”

An early, iconic scheme there, coastal park Gardens by the Bay was announced in 2005 and was designed by UK landscape architects Grant Associates. “In Singapore, land reclamation and greening policies balance high-density, built-up environments with vertical green spaces in the form of sky gardens and rooftop urban farms that cultivate fruit and vegetables and help lower the environmental impact of urban development,” says Jason Pomeroy, founder of Singapore-based Pomeroy Studio, which specialises in sustainable architecture.

An early adopter of biophilia in the UK is interior designer Oliver Heath, one of the designers in the original home-makeover TV series Changing Rooms, and now an expert in the field. He inspired Planted, an event co-founded by Deborah Spencer, who established influential design fair Designjunction several years ago, and Sam Peters, held during the London Design Festival last September.

“For years, I’d been aware of the wasteful culture surrounding events, largely through running Designjunction,” says Spencer. “When a friend introduced us to Oliver and biophilic design in 2019, it was a Eureka moment. It provided us with evidence-based arguments as to why we should be designing our homes, workspaces and recreational spaces with nature in mind. At Planted, we ran a talks programme themed ‘Delivering green cities in a post-pandemic world’, with the first talk explaining why biophilic design matters now, hosted by Oliver.”

Now the event is to be transplanted to picturesque estate Stourhead on the Wiltshire-Somerset border. Run in partnership with the National Trust, it will take place from April 30 to May 2. Billing itself as the first zero-waste design event (all of its installations will be designed to be reused or recycled), it will showcase “nature-based design” and host a programme of talks led by Peters and Heath.

Heath tells us that a childhood spent “running wild, climbing trees and building dens” in countryside near Brighton sparked his interest in biophilia. “Aged 10, I wanted to be an architect. Later, when working on Changing Rooms, I felt there wasn’t enough discussion around sustainability, so I made it my mission to talk about how design could reduce its impact on the environment and boost wellbeing. Over time, I discovered biophilic design.”

He identifies three core characteristics of biophilia: “Direct contact with nature through elements, such as water, trees, plants, light and fresh air; indirect contact with nature, evoking it through materials, colours, textures, shapes and patterns; and human-spatial response – creating spaces that stimulate but also calm and restore.” He adds: “In areas with access to nature, there is seven to eight percent less crime, while property prices command an increase of four to five percent.”

The notion that biophilia yields scientifically proven economic benefits underpins Plantworks, a new-build office in King’s Cross, designed to allow employees at work to harvest fruit and veg from its plants, including olives, rosemary, strawberries and carrots. Completed in 2021, the building was co-designed by London-based Marek Wojciechowski Architects and New York-based urban farm designers Kono Designs. Sam Wood of Marek Wojciechowski Architects, who led the project, says a renewed appreciation of nature spurred by the pandemic partly informed its design: “With the current era of working from home highlighting the need for nature and biodiversity in our lives, environmental design was the focus of Plantworks.”

The brainchild of Clemente Cappello, chair of investment management firm Sturgeon Capital, the venture seems motivated as much by business-like pragmatism as by environmentalist goals: “Optimising an office environment for humans through cultivating plants results in higher productivity and encourages teamwork,” he says.

Plantworks’ website cites the following statistics from Harvard’s COGFX research: “Green workspace increases cognitive functions substantially: 31% improvement in strategy, 38% in focus, 44% in applied activity and 37% in crisis management.” It’s hard to know how such research can be precisely quantified but it’s now widely believed that it improves productivity.

Hospital windows that look on to plants are also widely seen as speeding up the healing process of patients. Arguably, Finland’s 1930s Paimio Sanatorium, designed by Alvar and Aino Aalto and surrounded by forests, is a seminal example of biophilic architecture. It was designed for tuberculosis patients who were pulled out in their beds onto sunning balconies in the belief that clean air and sunshine helped to cure them.

The Aaltos also designed the building’s furniture, including the ergonomic Paimio chaise longue, whose pleasingly curvilinear form resulted in a new, more human strand of modernism – organic modernism. Made of wood, deemed by the Aaltos to be warmer and more tactile than cold, tubular metal favoured by many machine age-worshipping modernists, the chair was designed to make it easier for patients to breath.

Biophilia can be said to be reflected in contemporary furniture, such as Tasmanian-born, London-based designer Brodie Neill’s dining table ReCoil. This is made of veneer taken from trees salvaged from an area of virgin forest in Tasmania that was flooded in the 1980s during the creation of a hydroelectricity scheme. And Neill’s Cowrie chair, inspired by seashells, graces a London house designed by David Adjaye, which features plant-filled courtyards that bring its occupants into close contact with nature.

Another nature-inspired London interior is the riverside Hoopla apartment by architect Debbie Flevotomou, who is influenced by the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller and curvaceous buildings of Zaha Hadid.

A focal point in Hoopla is its wall-mounted, boldly curvilinear, abstract feature, evocative of waves, a serpentine river or double helix, depending on how the viewer interprets it. This ambiguous element expresses a lesser-known aspect of biophilic design, which Flevotomou defines as “the drama of the unexpected experienced in nature – the apartment’s biophilic elements mimic nature’s ability to surprise in the form of dramatic effects.”

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto