The UK fair for contemporary craft and design made an upbeat return to London’s Somerset House for the first time since the onset of the pandemic

The excitement felt by the gallerists at this year’s Collect was palpable. Last year was necessarily a digital affair and its return to Somerset House – 31 galleries participated physically this year – was widely welcomed.

Arguably, there is no substitute for a live event, where visitors can examine the many finely crafted pieces on display and to speak to gallery owners and designers in the flesh. “We’ve been showing at Collect since 2014,” says Andrea Harari, director of west-London gallery Jaggedart. Asked what the key attractions of Collect are for her, she says: “It gives great exposure to artists. Visitors are very knowledgeable. It’s a good way to meet curators and collectors, too. And after a two-year gap since Collect was last a physical fair, it’s wonderful to reconnect with people and show works in the flesh as this what it’s all about.”

Founded in 2004 and organised by the UK Crafts Council, Collect takes place at Somerset House. The venue is a big draw, its stately interiors with enormous windows overlooking the Thames providing an elegantly proportioned, spacious setting for objects made of an ever-widening spectrum of media, including ceramics, glass, furniture, tapestry, metalwork and jewellery. The physical show concluded on February 27 but it can be seen on the virtual galleries of digital platform Artsy.net until March 6 (one advantage, at least, of the digital version of the fair – and nine galleries are exhibiting online only).

At the stand of gallery Cavaliero Finn, co-founded by Juliana Cavaliero and Debra Finn, which curates exhibitions in London and the South West, I spotted the intriguingly patterned ceramic vessels of Frances Priest. These recall Islamic ceramic tiles, though in fact make broader references. Her eclectic approach springs from one of her biggest inspirations, a compendium of patterns from around the world compiled by Victorian architect and designer Owen Jones. “Frances’s father gave her a copy of it when she was a child and its many patterns fascinated her,” explains Finn.

The starting point for her vessels is drawings, which she transfers on to hand-built or press-moulded clay vessels when they are leather-hard with the aid of stencils and graph paper. Using a scalpel or aluminium stamps, she incises the outlines of the patterns into the clay. Once the vessels are fired, she highlights the outlines with oxide washes and applies layers of glaze and slips to the areas in between to create varying surface textures. Her pieces at Collect are from her Kirkcaldy Patterns series, inspired by research she conducted into turn-of-the-20th-century pattern books of linoleum patterns produced in linoleum factories in Kirkcaldy, Scotland.

It gives great exposure to artists. Visitors are very knowledgeable. It’s a good way to meet curators and collectors, too.

Andrea Harari, director of Jaggedart

Jaggedart showed the ceramics of Charlotte Hodes, whose forms are reminiscent of Neoclassical vases, yet look contemporary and have feminist overtones. Hodes is also a painter, and creates paper cutout-based pieces. Gallery director Harari says: “Charlotte uses ceramics as a canvas onto which she superimposes silhouettes of female figures.” She adds: “Her work references how women have been depicted on vases throughout the history of the decorative arts.”

The stand of west-London gallery Flow showcased ceramics by Paul Philp, Akiko Hirai and Cécile Dalardier, and glass bowls by Celia Dowson, displayed on furniture by Fred Rigby.

“We designed the space to create a feeling of a home,” says gallery founder Yvonna Demczynska, her rationale presumably being that her stand’s unusual design helped visitors and collectors to visualise how the pieces might look in their own homes.

In contrast to Dowson’s minimalist glass vessels – which come in delicate, graduated tones of cranberry, grass green and a smoky blue – the pieces here had a raw, organic aesthetic. Rigby’s furniture is monolithic and curvilinear, while Dalardier’s pique-fleur vases have a freeform look with uneven, rugged surfaces; some contain hollow protrusions into which flower stems are placed, making each one stand out more than if the flowers were arranged in a bunch. The protrusions surround shallow pools of water, which Dalardier considers integral to her designs.

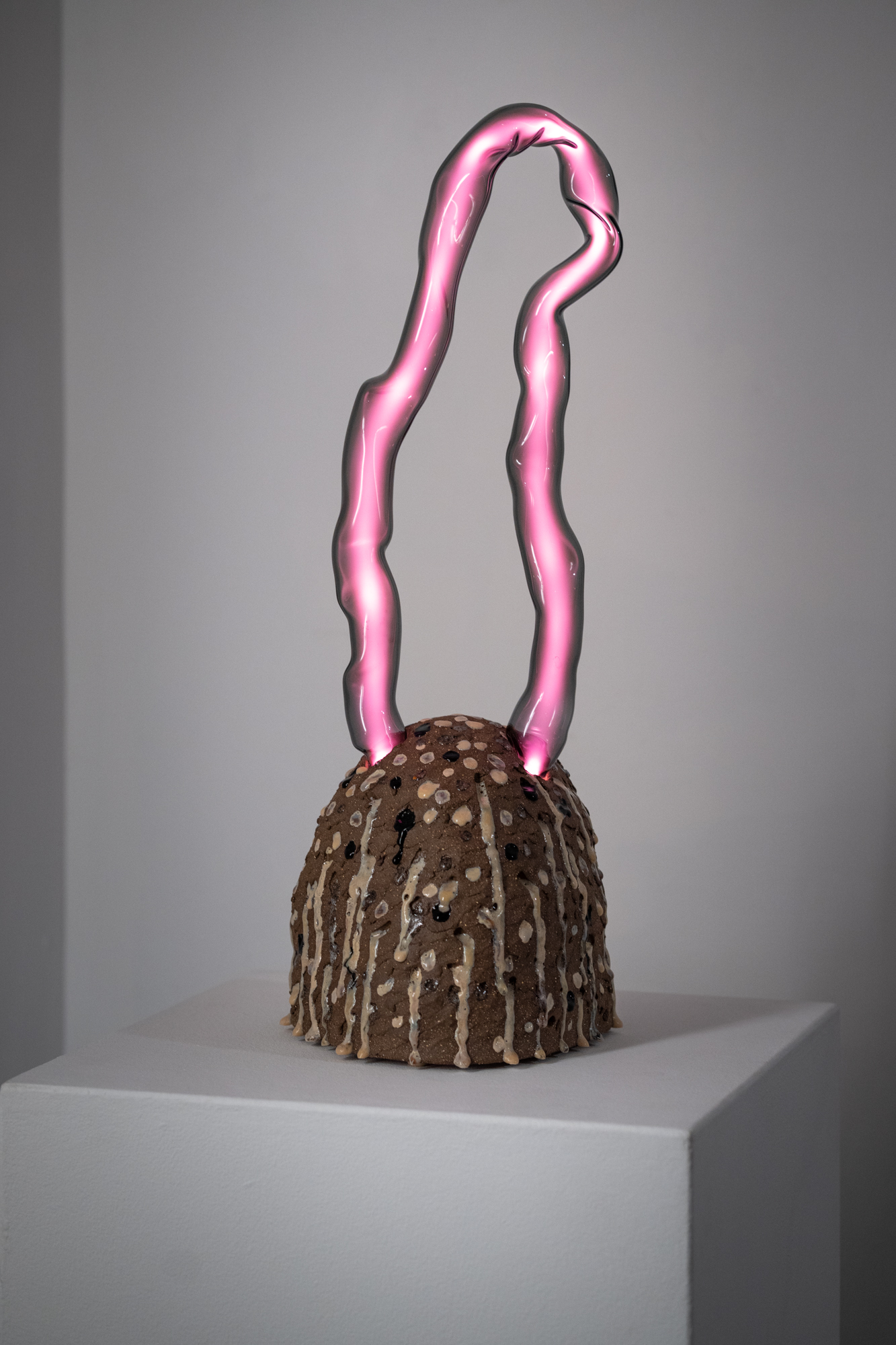

Free-form ceramics were also in evidence at the stand of decidedly funky gallery House on Mars. The pieces on show had a postmodern or pop feel that contrasted refreshingly with the formality of Somerset House, accentuated by the views across the river of the brutalist Southbank Centre.

Standout pieces included Attua Aparicio’s idiosyncratic, hybrid work, including her Minifundium Cone and Rod lamp of 2019 – a hand-made ceramic cone diagonally impaled by a waste borosilicate glass rod – and her Polypore Shelf of 2022 – a dual-functional shelving unit-cum-lamp with wooden shelves of varying lengths attached to a stoneware conical form crowned by light with a borosilicate glass diffuser.

The glazes on Minifundium Cone and Rod lamp look visceral yet decorative, thanks to their delicious ice-cream tones and glossy, dribbling glazes; and the artist explained to us the thinking behind them: “I test out glazes on ceramics to see how they interact when fired,” says Aparcio. “Ceramics are often fired at least twice, which is wasteful. I try to fire my ceramics just once as it’s more sustainable.”

Another exhibitor, Charles Burnand Gallery, showed Alexandra Champalimaud’s Herron Settee, with a black mica frame and polar bear-white upholstery in alpaca bouclé fabric, inspired by North American glaciers. The gallery is named after the grandfather of its founder Simon Stewart, who will open a gallery in Fitzrovia in April. Also on show here was Mia Jung’s oval, paradoxical Cloud Mirror – you can’t see your reflection in it. This unashamedly decorative, romantic piece is made of Murano glass coated with 24-carat gold.

Similarly alluring – and closer to fine art than traditional craft – were the wall-hung, embroidered panels of Cecilia Charlton at Candida Stevens Gallery, which reinterpret this traditional technique in a thoroughly contemporary way. This London-based, American artist’s work recalls the needlepoint-upholstered kneelers found in churches. The unique character of these pieces that feature trippy patterns in acid colours rests on their unlikely fusion of ecclesiastical and psychedelic associations. “The pieces are inspired by bargello, a needlepoint technique, churches I’ve visited in Florence and Venice and stained glass,” says Charlton. “I feel there’s a similarity between craft created meditatively in a monastic setting and 1960s and 1970s psychedelia – a kind of transcendence.”

In a not dissimilar vein was London-based, Mexican artist Fernando Laposse’s The Dogs bench, displayed at Sarah Myerscough Gallery. This eccentric, shaggy, sisal-covered seat conceals any sign of a dog’s head or tail. To put his humorous approach into context, in 2019 Laposse suspended gigantic sloths and hammocks dyed bright pink, using natural dye cochineal, from trees, lampposts and buildings throughout Miami’s Design District.

Craft can often be rather earnest but, as the work of Laposse, Charlton, Aparicio and several others who showed at Collect highlighted, it can also be witty and ironic. Certainly, such exuberant pieces contributed to the upbeat mood of what turned out to be a buzzy reunion of gallerists, collectors and design fans after a long period of isolation and restricted human interaction.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto