Since 1888, the beautiful, delicate glassware of René Lalique and the company he founded has been coveted for its beauty and craftsmanship. Effect Magazine’s Dominic Lutyens visits the maker’s French glassworks to find out how their reputation has endured and what they plan for the future.

In 2022, the world marked the 100th anniversary of jewellery and glass designer René Lalique’s glassworks at Wingen-sur-Mode in Alsace, France, a town so sleepy it feels like a village. At the time, Lalique’s decision to manufacture its goods there might have seemed surprising, given the designer already had a shop in Paris’ elegant Opéra district that sold fabulously flamboyant jewellery to a largely avant-garde, metropolitan clientele.

But Lalique (1860-1945) shrewdly calculated that for the brand to grow and take on large-volume production, this heavily forested spot was the perfect location for his factory at a time when glassworks were powered by wood-fired kilns. And the town’s railway station would help him to transport his wares worldwide.

The brand indeed proved an international success. Today, the factory makes 350,000–400,0000 pieces each year and Lalique items have been collected by luminaries from Elton John to Bill Clinton and Karl Lagerfeld. Vintage and antique Lalique pieces fetch high prices – the 1910 L’Idylle perfume bottle sold for $190,000 a couple of years ago at auction in Japan.

The life of René Lalique

Lalique was born in Aÿ, in France’s Champagne region. His family moved to Paris soon after, though regular visits back to to his grandfather’s house in Aÿ, where he was forever observing and sketching the natural world, proved a formative experience. Lalique was precociously passionate about art and design, attending evening classes at Paris’s École des Arts Décoratifs. From 16 to 18, he studied at the Sydenham School of Art in southeast London, where he was greatly influenced by the British Arts and Crafts movement. Around this time, he was apprenticed to Parisian jeweller Louis Aucoc, later freelancing for brands such as Boucheron and Cartier.

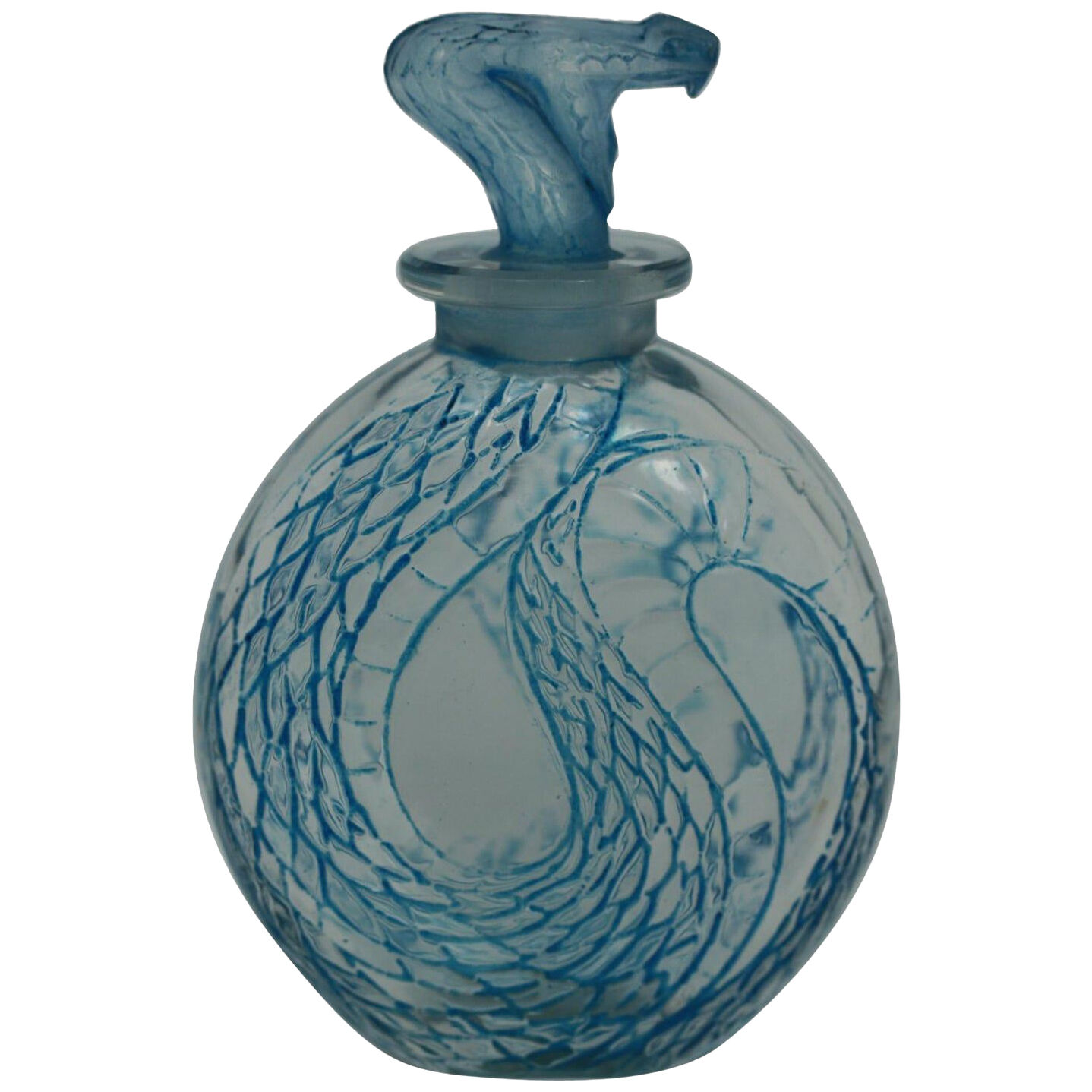

In 1905, he opened a shop at Paris’s ultra-chic Place Vendôme, selling his jewellery and earliest glass pieces. It was near the shop of Corsican perfumer François Coty, who, sensing that a scent bottle’s design contributed to its success, enlisted Lalique to create bottles for his perfumes. Lalique also designed scent bottles for Roger & Gallet and the House of Worth. Many of his bottles featured show-stopping stoppers, picturing anemones or careening swallows, which became favourite Lalique motifs. Lalique liked to combine clear and frosted glass on the same design, a hallmark of the brand to this day. Another attraction of Lalique glass and the patterns adorning it was how they interacted with light – an interest that earned him the moniker Sculpteur de Lumière.

As well as glass vases, bowls, decanters, plates, decorative centrepieces and chandeliers, in 1928 Lalique produced architectural glass panels for the Orient Express and for the Art Deco Fumoir Bar at Claridge’s in London. He also designed the similarly large-scale Poisson Fountain featuring leaping fish in frosted glass in the grand entrance to London’s Savoy Hotel. Other large-scale projects of the period include Lalique’s glass columns for the prestigious 1930s French cruise liner SS Normandie.

And Lalique produced 29 car mascots – placed at the front of a car’s bonnet – representing female forms, animals and birds in opalescent or frosted glass, some illuminated by lightbulbs powered by the car’s engine.

Art Nouveau

Lalique was an innovative and visionary designer, who initially specialised in the brazenly modern, sensual Art Nouveau style that reigned from around 1890 to 1910. As its name suggests, this international movement in architecture and the decorative arts was forward-looking: it rejected past styles which its practitioners deemed stale and irrelevant to the dawning new century.

That said, Art Nouveau designers, including Lalique, were inspired by some past periods and styles, chiefly by ancient Greece, Japonisme, and the Italian Renaissance as well as the late 19th-century arts movement Symbolism, which reacted against mundane realism in favour of the imagination and spirituality.

Art Nouveau was inspired by nature but represented it in a very stylised way, characterised by asymmetry and sinuous lines, also known as whiplash. Art Nouveau designers relished such motifs as flora and fauna and languid nymphs with locks flowing as freely as swirling currents in a fast-moving river.

The movement flourished in France, and Lalique – a key figure of the movement – carved a niche for himself producing exquisitely crafted, imaginative jewellery such as chokers, tiaras and ornamental hair combs that often incorporated nature’s more sinister creatures, from flitting bats to predatory snakes. Yet he combined the menacing with the beautiful to edgy effect: on one of his hat pins, lifelike wasps crawl on an opal representing a nectar-laden flower, framed by prickly thorns.

Lalique was a savvy self-publicist as well as an aesthete. A participant of the international Paris Exposition of 1900, he wowed visitors with an original display stand consisting of large bronze female figures metamorphosing into butterflies from which he hung his jewellery – a far more eye-catching display than if laid flat.

Unsurprisingly, Lalique attracted individualistic customers who shared his love of the exotic. These mainly included wealthy, fashionable society women and stars of the theatre or opera, notably cult actress and style icon Sarah Bernhardt, who sometimes slept in a satin-lined coffin that she kept in her bedroom. Lalique gifted Bernhardt her spectacular stage jewellery – a marketing ploy akin to today’s use of influencers to promote products. Bernhardt later introduced him to British-Armenian businessman and art collector Calouste Gulbenkian, who commissioned more than 140 works from Lalique.

Art Deco

Lalique’s daughter Suzanne Lalique-Haviland – a successful theatre and costume designer – worked on many bowls and vases attributed to her father, René. Her bold, geometric style is credited with helping to steer Lalique’s aesthetic away from Art Nouveau towards its more streamlined successor, Art Deco, which René was at first reluctant to embrace – despite the disdain commonly held by the French for Art Nouveau (described by its detractors at the time as “Style Nouille” – Pasta Style, says a guide at the Musée Lalique).

Lalique’s presence at the 1925 fair, Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes – which spawned the term Art Deco – signalled his commitment to this angular aesthetic; and his contribution to the fair was a gigantic, futuristic glass fountain adorned with glass statuettes depicting female figures from Ancient Greek mythology, illuminated from within.

Lalique today

Today, Musée Lalique, also in Wingen-sur-Moder, displays over 650 pieces chronologically showcasing the brand’s output of jewellery, glassware and the crystalware since the late 1940s. The museum also highlights the input of René’s children – Suzanne Lalique-Haviland and her brother Marc Lalique, who joined his father’s company in 1922, taking over the business after his father’s death in 1945.

The company remained in the Lalique family until 1996, and is now owned by Swiss entrepreneur Silvio Denz. Today, the growing Lalique empire includes an interior design studio and hotels, such as the five-star Villa René Lalique in Wingen-sur-Moden (complete with its own two-Michelin-starred restaurant), as well as The Glenturret Lalique, a restaurant in Perthshire, Scotland.

The complex production of Lalique crystalware in today’s 20,000-square-foot factory almost fetishises perfectionism. Lalique has always fabricated its own moulds from steel or cast iron; the factory holds 6,000 of these including one used to produce Lalique’s best-selling Bacchantes vase, created in 1927. Glassmakers in the current workshops bring molten glass to furnaces heated to 1,400℃ – an operation conducted with choreographed precision.

“A master glassmaker takes 10 years to train,” says Denz, who admits that one challenge the company faces is a dearth of young craftspeople interested in learning such highly specialist craft skills.

After the molten crystal is cast in the moulds using such techniques as blowing or pressing, it is annealed (heated, then cooled) over a period of a week to prevent thermal shock causing it to crack or explode. Pieces are then retouched, sculpted and engraved manually, then polished or satin-finished by sandblasting them or immersing them in acid baths.

The riskiest process in the factory is the lost-wax technique, utilised when making the brand’s most expensive or limited-edition sculptures. This necessitates painstaking hand-polishing following many stages of pouring and moulding, which increase the chances of items being damaged. The technique has been used over the years to create works designed for Lalique by high-profile designers such as Arik Levy, Zaha Hadid and Damien Hirst. And the factory are marking their 100th anniversary by collaborating with American artist James Turrell.

To many Lalique fans, however, some of the older, classic designs may well be the most appealing – from the clear and frosted crystal Mossi vase of 1933, originally designed in clear glass by René, to his 1930 Mûres (blackberries) vase.

Mûres recalls The Sleeping Beauty, in which the prince hacks his way through bramble thickets before awakening the slumbering princess. This might seem a fanciful interpretation but it’s perhaps not wide of the mark, given the brand’s description of the piece: “The Mûres vase exhibits an abundance of berries jealously protected by intertwined brambles… an invitation to a dreamlike walk in the undergrowth.” Described like this, the vase really does sound like something that sprang from the colourful imagination of its creator, René Lalique.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto