Anaïs Bléhaut studied art before architecture, but even after immersing herself in both disciplines, it took her a long time to decide which she wanted to pursue as a career.

“In the end, I chose architecture because I recoil from the constant personal interrogation demanded by art. I don’t relish continually excavating myself, embracing my dark areas, and searching for an inner genius,” she says. “I’m too interested in other people and what makes them tick. I love the dialogue of architecture.”

But her passion for art never waned, so when Daab, the architecture practice she set up with her partner Dennis Austin in 2014, has a commission to design an interior around specific artworks, it’s the best of both worlds for Bléhaut.

“It’s fascinating to discover new pieces and what their owners feel about them – artworks that are masterpieces for the client, even if the world doesn’t necessarily label them as such,” she tells Effect.

Of course, most clients do not approach the practice with the idea of designing their ideal home around particular pieces – most often, it is Daab that gently steers them in this direction.

“When we are outlining the project brief, we ask the client for photographs of their favourite artworks and other cherished objects,” says Bléhaut. “The images can reveal a side of themselves of which they might not be aware. Sometimes, the things they share are quite radical – we’ve had photographs of people’s dresses and shoe collections – and sometimes you might describe the items as cute. But the point is, these objects hold meaning for the client.”

When we are outlining the project brief, we ask the client for photographs of their favourite artworks and other cherished objects. The images can reveal a side of themselves of which they might not be aware.

Anaïs Bléhaut, Daab Design

The fossilised rhinoceros skull at the centre of a design scheme the practice is working on right now certainly falls into the radical camp. It belongs to a jeweller who collects particularly old fossils, and when he showed it to Bléhaut, she knew immediately it was a vital visual clue. “His day job was clearly also his passion,” she says. “He adores stones and minerals.”

So he might, but standing at over a metre in height, the animal’s skull dominates the main living space of the jeweller’s 1,100-square-foot London apartment so completely that it absolutely had to be the only stone on show, says Bléhaut. “We’re using a lot of raw timber in the project and on as large a scale as possible,” she says. “The floorboards are five metres long and 30 cm wide and the apartment’s three-metre-high doorways will be lined with timber to give the impression of portals. Together, these elements will say ‘mega’. In fact, we’ve called the project Broad.”

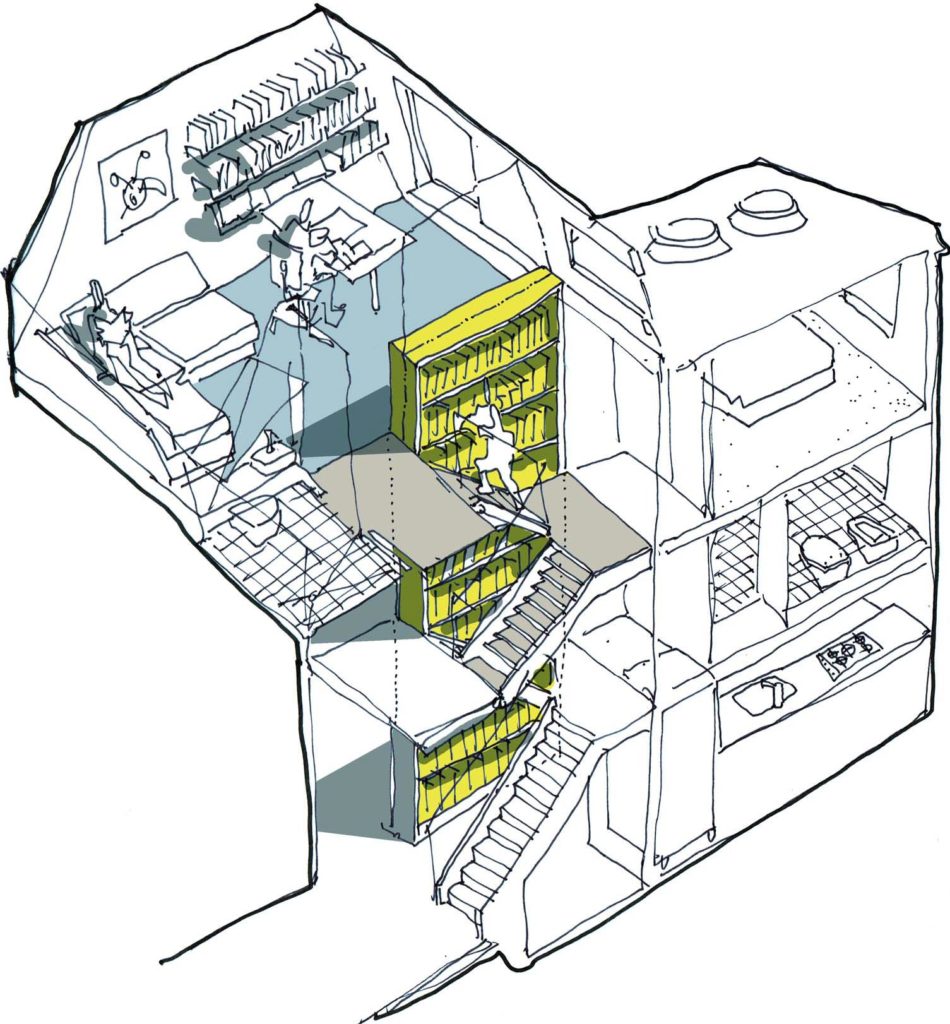

In another corner of London, the practice has designed an interior which says: literature, art, music. The house is experienced as a series of unfolding spaces that are connected by an open-tread staircase, flanked by a three-storey bookcase. Golden Stair has a place to listen to music and lots of wall space for paintings.

“People who love literature also love the square cube that is a book – and this client has lots of them, so we designed the scheme around his library,” says Bléhaut. “Rather than rooms, he wanted spaces in which to relax and focus on his interests, and for music and his big art collection to animate those spaces.”

Art – specifically Julian Opie’s – was the design-cue for the monochrome interior the studio created for a Regency townhouse in Kensington. “This family, which is not originally from London, is completely in love with Opie’s work to the extent that we believe his paintings of the city helped them settle here,” says Bléhaut.

“We decided early on that the scheme would be mainly black and white, and that the black had to be a rich Opie-black. We didn’t want to introduce colours that would compete with or distract from his works. His art is our departure point.”

Put another way, part of the design story had already been written. “And this is exactly how I like to work,” says Bléhaut. “I don’t want to impose my taste on clients. My job is lending my competencies so they can realise theirs.”

As well as interior schemes for individual houses, this small architecture practice – “there are five of us, though we’d like to grow a little” – also does master-planning, rail infrastructure projects, and conservation work. And Bléhaut is working on a guide for locals in Battersea, where she and Austin live, on how to look after the heritage of their homes. A portfolio, you could say, that reflects the biographies and work experience of the couple.

Bléhaut trained in Paris and Rome, and had 20 years of designing award-winning projects in Europe and America with Will Alsop and HOK before setting up Daab. Austin trained in New York and has held positions at RSH+P, l’ADP, Santiago Calatrava and Rafael Viñoly.

“We apply our large practice knowledge in a studio format,” she says, “and we believe firmly that the creative process relies on stimuli from multiple sources.”

Conservation work is so interesting, she believes, because it comes with these stimuli plus two clients – the flesh-and-blood one and the building itself. “You need to understand the site, its condition, the requisite repairs and what your client wants. If you try to fit everything together in the rational way an engineer might, you’ll fail because it’s too complex. That’s where architectural intuition comes in. That same intuition you use when you’re designing someone’s home around an art piece. You need to capture its spirit.”

That’s where architectural intuition comes in – that same intuition you use when you’re designing someone’s home around an art piece. You need to capture its spirit.

Anaïs Bléhaut

Right now, the studio is capturing the spirt of an apartment in the Harrods Village development in Barnes, a former warehouse built in 1894 to store furniture too large to display in the famous Knightsbridge department store. The Grade II-listed building was converted into apartments in the 1990s.

“We’ve designed the apartment so it celebrates London at the turn of the 20th century, with very broad floorboards and exposing some of the impeccable brickwork which had been covered behind a lot of plasterboard.”

The studio also recently completed two listed buildings for private clients. Unearthed Vault is a two-bedroom basement flat with a nook kitchen that now stands in what remains of a concrete store room used for many years as a vault by art dealers. All of the building’s Georgian features including its windows, outdoor larder, wooden doors, architraves and York stone floors have been restored, a process that involved working with structural engineers and an archaeologist.

And on Guild, the practice peeled back years of disrespectful interventions to restore the masonry, ironmongery, plaster work, panelling and woodwork of a Georgian townhouse that is now a contemporary home for a family of seven. A new staircase connects a cellar and lower sitting room with a high-tech kitchen and living room. In short, a dialogue between the past and present. Dialogue being the thing about architecture that Anaïs Bléhaut loves the most.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto