Large-scale lighting appeals to interior designers for giving any room a dramatic, resplendent focal point. What’s more, when such bold lighting is bespoke it gives a space individuality. Less obviously, super-sized lighting is commonly – and increasingly – used in interiors all over the world because it has the potential to look equally stunning when switched off, its sculptural qualities suddenly coming to the fore.

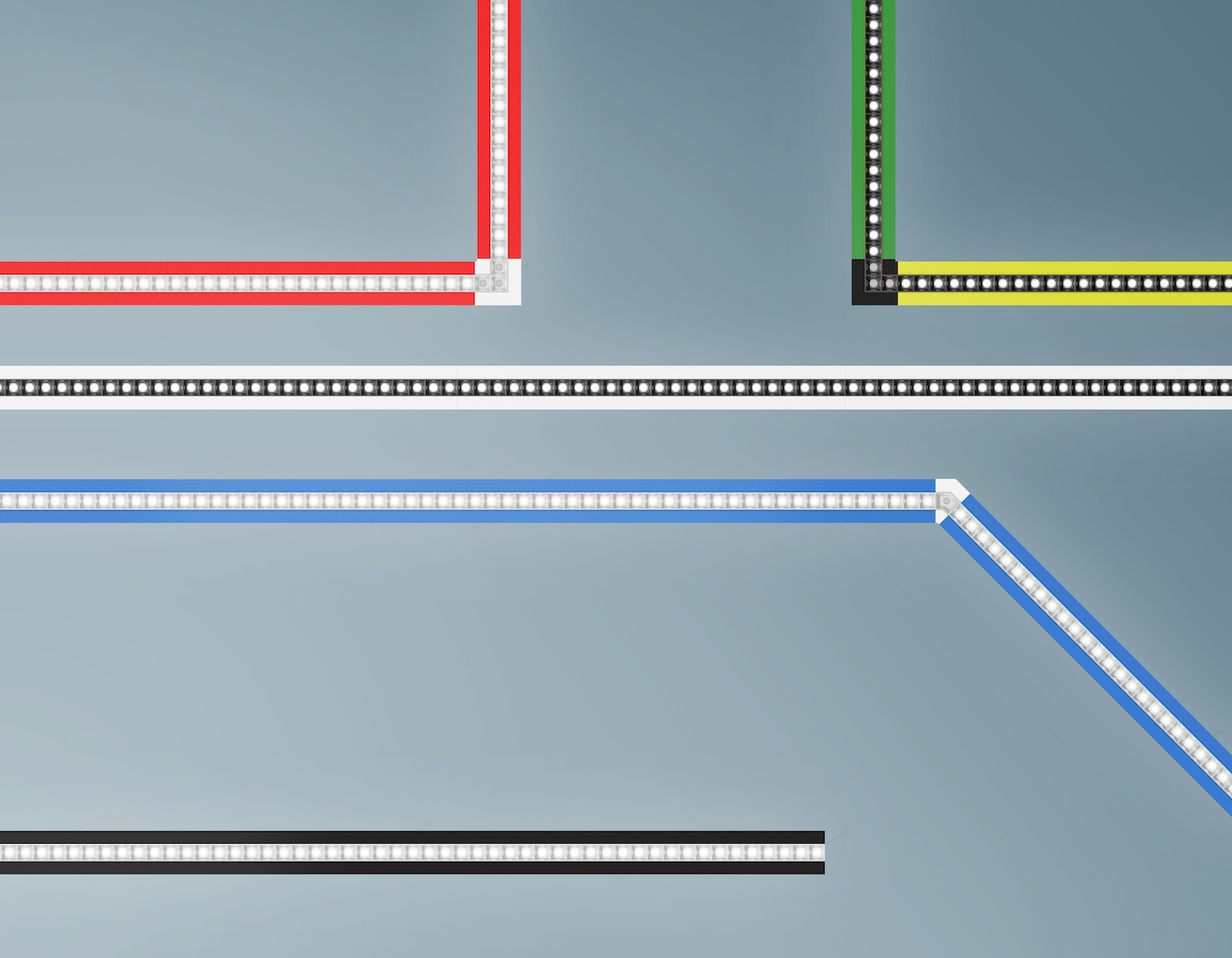

For lighting designers, creating wildly attention-grabbing lighting gives them freedom to dream up pieces that can take almost any conceivable form. The introduction of LEDs, which today are smaller than incandescent light bulbs (and more energy-efficient), has allowed for greater flexibility and experimentation in lighting design.

Of course, large-scale lighting has taken myriad forms for decades, offering innovative alternatives to classical chandeliers and archetypal lamps with simple shades. Modernist designers, from Japanese-American Isamu Noguchi, who was also a prolific sculptor, to French designer Serge Mouille, greatly expanded the possibilities of lighting design.

Noguchi, the subject of an exhibition at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, which ends on January 23, is most famous for his Akari lamps designed in the 1950s and made of washi paper derived from mulberry bark and bamboo. These assumed countless forms, from totemic structures to egg shapes and cubes. The paper shades conceal the light source, so the lamps aren’t harshly defined, instead casting a hazy, ethereal light. The Akari lights, which proved a worldwide hit, are manufactured now by Vitra and are still covetable.

Mouille, whose designs are also still sought-after, came up with a different approach. In 1953, he began making his elegantly minimalist – yet highly functional – lighting in black-painted metal, combining slender, insect-like arms and small, discreet shades. His wall-mounted lamps sometimes featured several arms that swing in various directions to illuminate different parts of a room.

A particularly spectacular example of sculptural lighting is found in Jane, a restaurant in Antwerp, which opened in 2014. Occupying a former chapel of a military hospital that retains many original features, it boasts an unmissable bespoke chandelier, created by Lebanese lighting specialist PSLab. Suspended from a soaring ceiling with flaking grey paint, it appears to explode, its multiple poles with crystal globes attached to each tip shooting in all directions.

Leading Vancouver and Berlin-based studio Bocci designs and manufactures lighting that is often modular, allowing more elements to be added to it, and sometimes vast, cascading down grand staircases. Anyone seeing one of these switched off could easily mistake it for an arresting sculpture or art installation.

The company invests heavily in research and development in its quest to push the boundaries of lighting, chiefly by experimenting with materials not normally associated with it. It has built its own glass studio devoted to investigating unconventional processes to help develop its products.

One of these, Bocci’s 73V pendant light, is made by blowing molten glass into folded, heat-resistant, ceramic-based fabric, which leaves behind an imprint of crinkly fabric on the glass. A more recent design, called 100, is created by amalgamating bubbles of molten glass. Once these have cooled, parts of their exterior are sliced off; the resulting forms are frosted, lit from within and cast a soft glow.

“When developing new methods for making forms, we routinely cut prototypes to learn about what’s happening inside,” says Bocci co-founder Omer Arbel. “But it occurred to us that the act of cutting can become part of the work, not just a learning exercise. With 100, we have exposed the most fascinating parts of the glass’s geometry.”

According to Italian architect and designer Mario Cucinella, the demand for monumental, sculptural lighting today is partly driven by a recognition that lighting influences how we perceive architecture physically and psychologically: “We now have a better understanding of how it improves our wellbeing.”

Moreover, he believes there’s a place for relatively neutral, less showy sculptural lighting, not least because it’s more adaptable to different styles of interior: “Just as there’s room for highly singular sculptural lighting, so there is for less ‘look-at-me’ designs, suitable for many settings.”

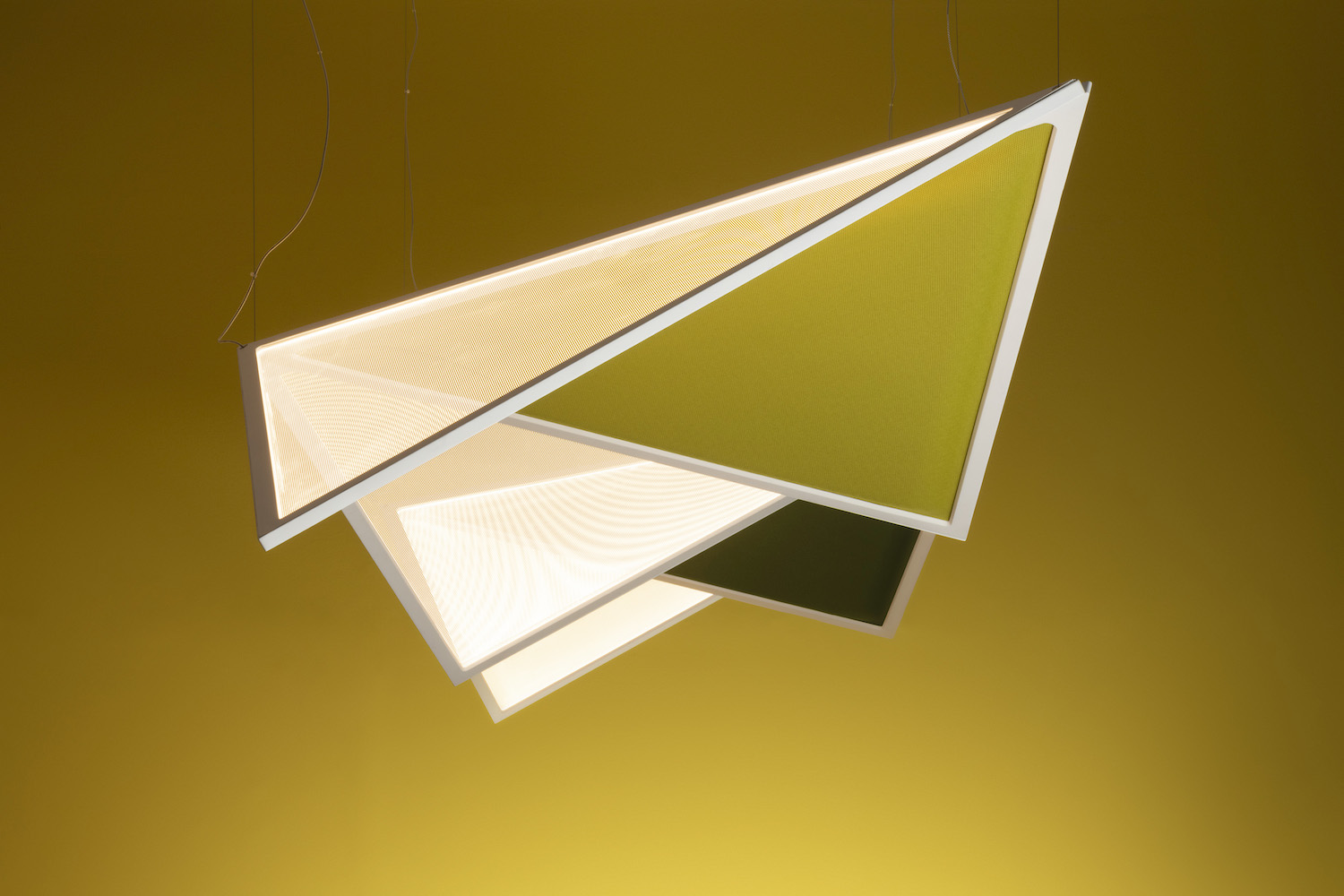

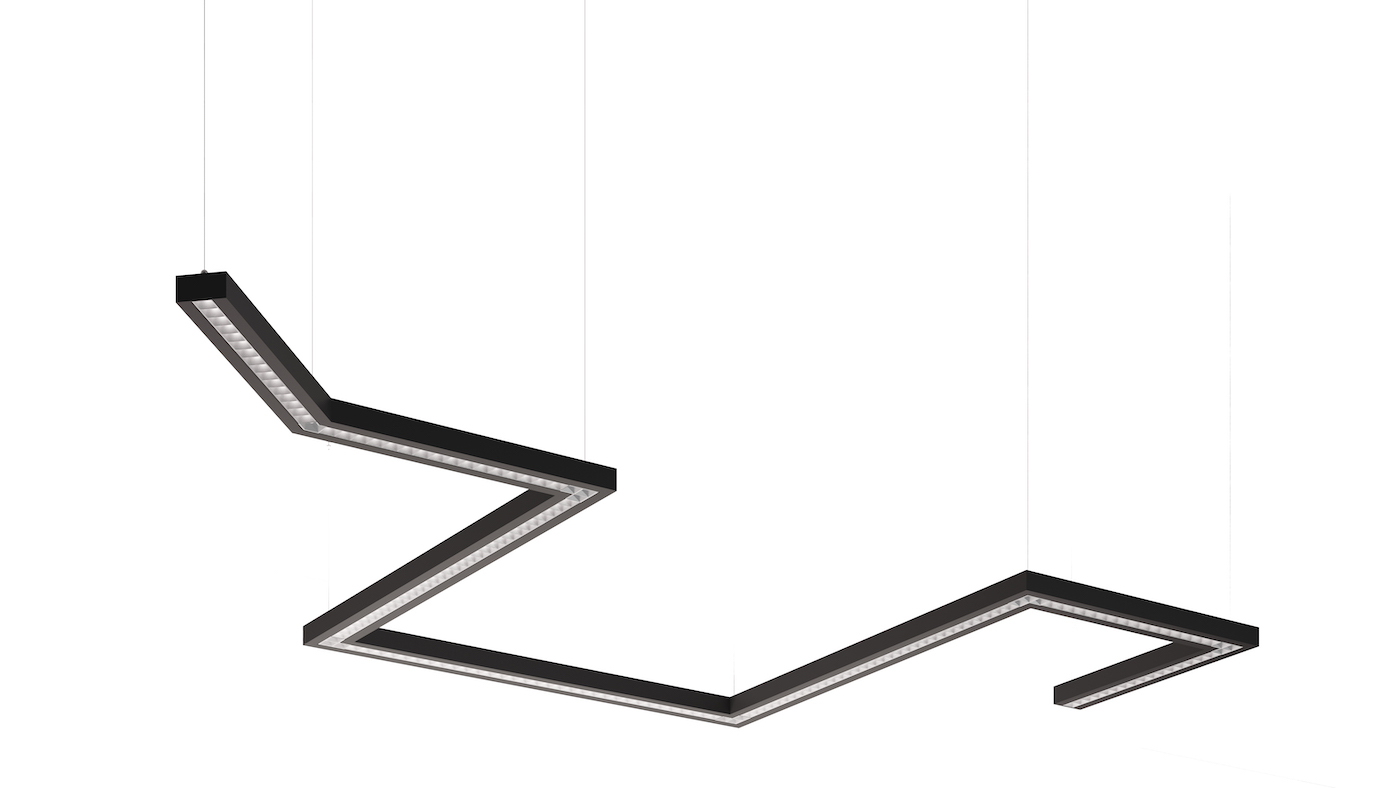

Cucinella has designed understated yet striking lighting for Italian brand Artemide, including the ceiling-hung Flexia, which is inspired by origami and its ability to make a piece of paper represent something different simply by folding it. Flexia, too, is transformed just by switching it on. “With Flexia, I wanted to explore how it could be transformed, when switched on, into an object apparently made of solid light. When switched off, it looks quite different – more ethereal.”

Cucinella’s comment on the interrelationship between lighting and architecture highlights another facet of imposing, sculptural lighting, namely that it’s an architectural intervention. And while an impressively large lighting feature might give a room an instant wow factor – especially if it’s a modular design that can be enlarged by multiplying its components – there are other aesthetic considerations to bear in mind. For example, will its shape and size harmonise with the architecture and proportions of the room it’s destined for?

Shalini Misra, interior designer and founder of her eponymous interior design practice, certainly thinks so. Describing the Gabriela pendant light by Royal Stranger, pictured above (for Design Buzz, Misra’s online shop for high-end design), she says: “Several Gabriela lights, arranged in a cluster to make a real statement, are hung in a recessed area fronted by an arched wall. This frames them perfectly.” She adds: “The lights are also suspended above a dining table with a round top, so there is a play of circles in this setting.”

Sculptural lighting is forever morphing, with designers constantly reimagining it. But although it’s often inventive, playful and eye-catching, it needs be chosen judiciously when installed in an interior. Rather than being dramatic for the sake of it, it is most successful when it forms a cohesive whole with its immediate surroundings, adding visual interest to a space – whether illuminated or not.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto