A global renaissance in skateboarding is leading to bold new skatepark designs, from coastal concrete shapeshifters to multi-storey skate cities with bespoke art, discovers Clare Dowdy in the third of our Design Subcultures series.

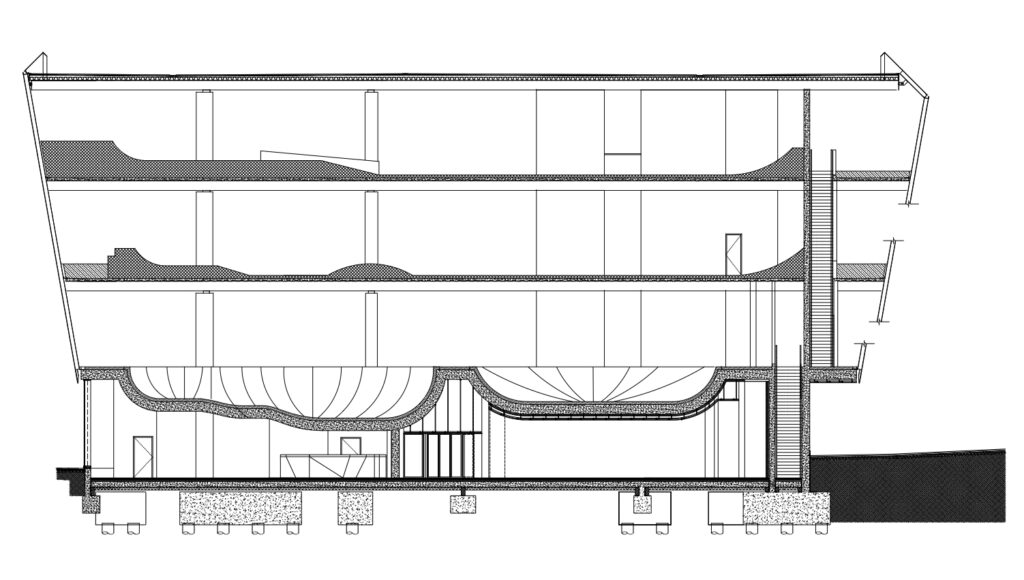

Can a small deprived seaside resort on the Kent coast reinvent itself into a skateboarders’ paradise? It’s attempting just that with the arrival of a £17m shiny, tapering, multi-storey indoor skatepark.

The F51 building is part of a resurgence in boarding (and ‘wheeled sports’ more broadly) around the world. There are now around 50m riders worldwide.

Over recent decades, the sport has gone from a fringe activity for social misfits to the mainstream, and even made its Olympic debut in Tokyo in 2021. Local authorities are at last embracing it as a healthy pastime and commissioning decent skate parks or – shock horror – occasionally encouraging skaters to use the existing urban environment.

In the early days, boarders had no option but to seek out skate-friendly areas in their neighbourhood – from steps and curbs to benches and rails. All of a sudden, street furniture came to have a new purpose. Then in the early 1970s, a drought caused the backyard swimming pools of California’s Dogtown to empty, and these too were repurposed by skaters. This phenomenon has gone on to inspire skatepark design around the world, including the concrete ‘bowl’ floor of F51. Designed and built by Maverick Industries, the lip of F51’s 2.9m-deep bowl is tiled, à la pool.

Maverick’s Russ Holbert points out that the modern-day skate park of spray concrete was also born out of the famous Burnside in Portland – a collection of structures built illegally under a bridge, which over time was adopted by the city and became a mecca for boarders.

How times have changed. In 2021, the US’s biggest skatepark opened in Des Moines. The 88,000-sq-ft Lauridsen Skatepark features a skateable art piece entitled WOW. Like F51, it’s centrally located, again telling boarders and non-boarders alike that their pastime has been accepted.

Historically, “skate parks have been out of town and unmanaged,” and can then get a bad reputation, says Guy Hollaway, architect of F51. That can lead to anti-social behaviour, which in turn gives the sport a bad reputation.

Despite the earlier poor image, skate parks, be they DIY or purpose-built, share a philosophy with these early experiences. It’s about the boarders’ relationship with the built environment – a relationship that’s a world apart from that of the rest of the population. “Where handrails, curbs and banks are at first glance part of a system of mundane signals, skateboarding transforms these elements into sites of energetic pleasure,” says Iain Borden in his book Skateboarding, Space and the City: Architecture and the Body. “It is this focus on texture, surface and tactility which gives skaters a different kind of urban and architectural knowledge.”

This means riders think in terms of an alternative ranking of architecture. “That’s something which is really important for architects to know,” says Borden. “Your buildings may get used, interpreted and understood by a completely different set of criteria.”

Boarders “map the city according to angled banks, smooth surfaces and noisy bits,” he adds. “It takes us back to this idea that we want to feel alive more in cities.”

A rider for more than 40 years, Borden is professor of architecture and urban culture at the Bartlett School of Architecture, and advised on the brief for F51.

The building’s third floor houses the ‘street’, designed and built by Cambian Action Sports in plywood. Typically, the street part of a skate park would be open and rectilinear, says Cambian’s Piers Chapman, and would have more segregation between riders and onlookers, with a start and finish point.

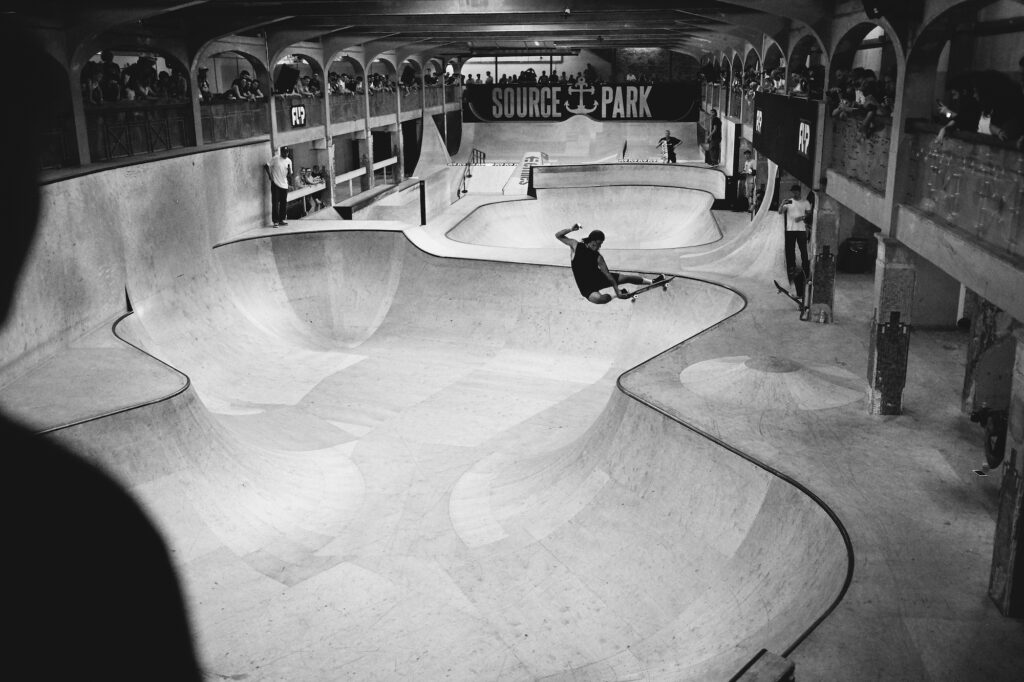

But F51’s structural columns meant that Cambian had to be more creative, planting features like steps and rails in positions which allow boarders to link a number of ‘tricks’ together to create many different ‘lines’ diagonally across the space. “That’s what makes the F51 street design so unique, because we’ve ended up with all these diagonals, so there’s a lot more to discover – and that’s the way in which the creativity will never end in the space,” says Chapman, whose firm was also behind the underground Source Park in the former derelict White Rock Baths of Hastings.

While the features and street furniture of a typical urban environment crop up in purpose-built parks, those same features often act as barriers for boarders looking for ‘spots’ in the real streets to ride. Some cities add skate stoppers (a piece of metal or notch) on benches, “putting up a physical barrier to riding a piece of furniture”, says Chapman.

But it’s time that cities were more inclusive and skate stoppers were done away with, believe the boarders. “It makes sense to cleverly design city centres and parks to accommodate boarders, because they’re going to use them anyway,” says Holbert at Maverick. “With good town planning, you can create spaces for all.”

And nowadays, the more enlightened cities are actively providing rideable and skateable architecture. Malmö in Sweden, whose official Skateboarding Coordinator liaises with City Hall, is held up as the place that has most embraced skate culture. Others, such as Melbourne, Innsbruck and – more recently – Hull are following suit.

But it’s not all about gritty urbanites. The sparsely-populated English county of Cornwall has adopted a welcoming approach to boarding. Maverick has built several schemes there, including St Ives (complete with a Barbara Hepworth-inspired loop-the-loop vortex).

While architects and furniture designers are users, inasmuch as they occupy buildings and sit on chairs, only boarders and others on wheels have this intensely visceral relationship with street furniture and the built environment. Which explains why the best park designers are riders themselves. “If you want to create facilities that are truly great, it makes sense to go to the people who have done that all their lives,” says Holbert. But what if these skate park creators were given the brief to design a bench, a walkway or even a structure for all of us to use? Now, there’s a thought.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto