What’s that strange building in your neighbourhood with CCTV and blacked-out windows? Effect Magazine speaks to Power House curator Clare Dowdy to find out, in the second of our Design Subcultures series.

If you’re reading this online, you’re using one. If the house next door looks a bit wrong and has blacked-out windows, your neighbour is one. Or if the vast edifice you’re driving past could enclose several airports and has no visible purpose, you’re next to one. Data centres: we all use them, but know surprisingly little about them.

And they’re getting closer: even a few kilometres out of town can render one less competitive due to the few extra milliseconds a data search might take (and on which margin stock markets might rise or fall), so they are increasingly moving into cities, among us, yet hidden, as if to discourage prying eyes or malicious intent.

These two different pressures – the need to hide them among us, and the need for vast capacity on the outskirts of civilisation – are creating their own strange grammar of design. Engineers and architects can spend whole careers immersed in them, and it’s not a stretch to think of these as belonging to a whole new design subculture.

Clare Dowdy recently curated Power House: the architecture of data centres exhibition at London’s Roca Gallery (catch it now as it ends soon). She tells us: “I’ve written about architecture for a couple of decades at least. And I just started realising that this new building, or typology, was starting to emerge. It became obvious that they were really important as buildings – we can’t manage without them. Yet they are largely overlooked.”

That they are overlooked is not an accident. “You wouldn’t know it was a data centre,” says Dowdy, “unless you spot the clues, which are blacked-out windows or reflective windows, security fencing, and very little branding on the building, because of this sense that the operators or the people who run those data centres want them to be fairly anonymous.”

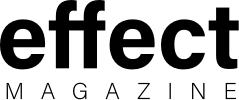

Why the secrecy? In part, it’s obvious: our lives and society have become almost entirely dependent on our data infrastructure, so the security stakes are high. But there’s also the sense that these vast nodes, avaricious for power, are society’s dirty little secret. Bitcoin-mining alone uses as much electricity in a year as the whole of Sweden, says the FT – to the extent that in China, so much coal was needed to power the data centres used for mining the cryptocurrency that when the price of coal rose, there was a corresponding rise in the value of Bitcoin. Every Google search, every YouTube video streamed, sparks up servers across the world, hoovering up power.

At the beginning of the 21st century, we are producing an architecture that is not constructed, or located, relative to human scale, but instead is a physical manifestation born out of, and subject to, global flows of information.

Donal Lally, ANNEX

Adding to this strangeness is the reality that these are not buildings created for humans. Donal Lally of ANNEX is quoted by the Power House exhibition as saying: “At the beginning of the 21st century, we are producing an architecture that is not constructed, or located, relative to human scale, but instead is a physical manifestation born out of, and subject to, global flows of information.”

While this is true, Dowdy counters that both their architecture and their desire for secrecy are gradually changing. “As their power issues are improved, they are being integrated more effectively onto the high street, and people are becoming a little bit more aware of them, and of how they fit into the urban fabric: how do they look – and how should they look?”

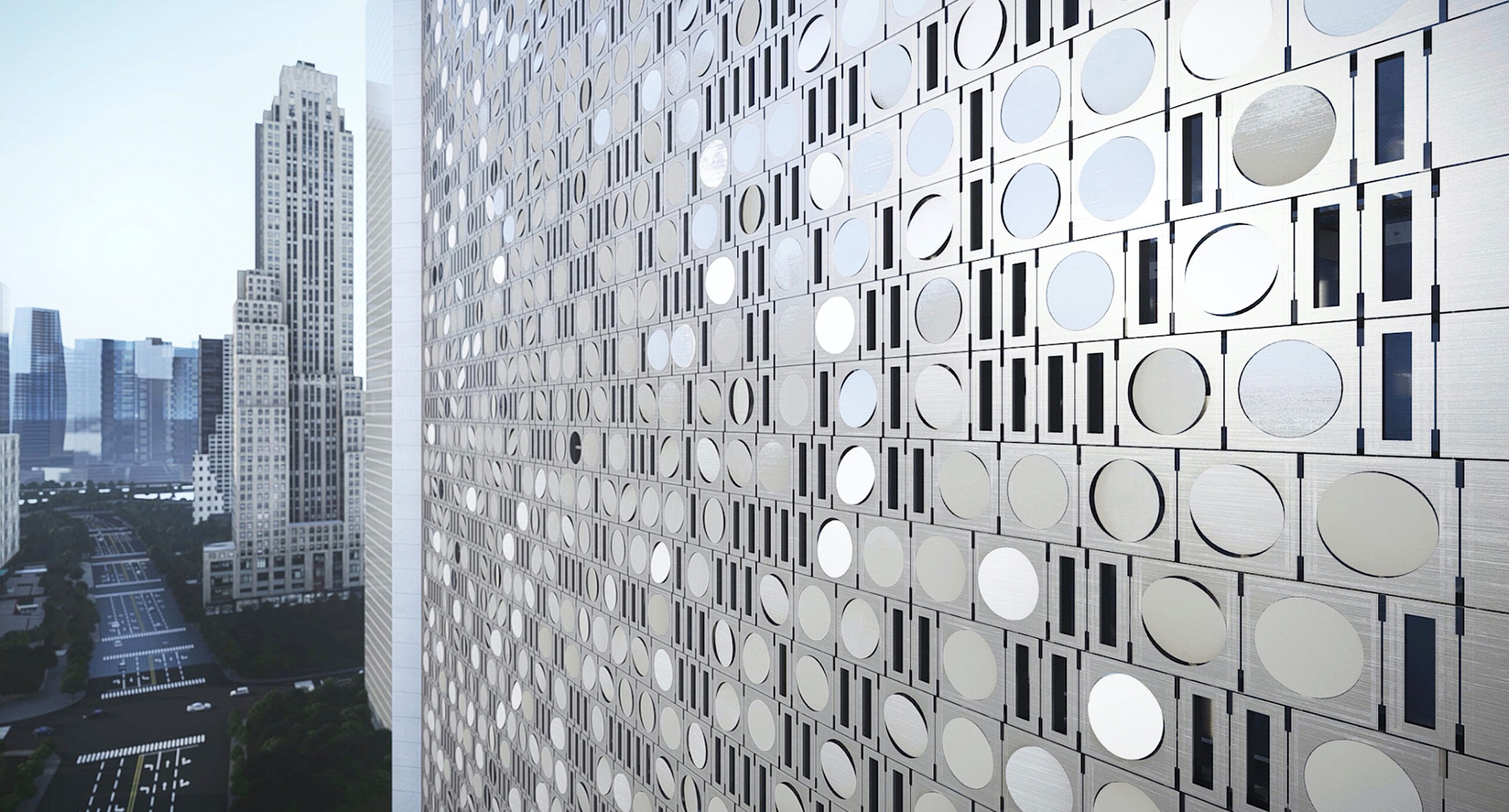

Currently, many urban data centres are retrofitted into old office buildings or department stores, but the questions Dowdy articulates are starting to be answered by architects less coy about hiding the true purpose of these buildings – such as Schneider+Schumacher’s Qianhai Telecommunication Centre, with digital-motif cladding designed to reflect the Shenzhen sunlight.

And this is not restricted to urban data-centres. Architects such as Snøhetta and Scott Brownrigg are increasingly bold in the designs they are advocating as data centres begin the long journey into the warm embrace of our collective awareness.

The key driver of many of these changes is power. Aside from the servers themselves, datacentres are designed around their huge power needs and cooling systems. And as power grid outages are an untenable risk, they need their own generators – and backup generators: essentially, their own power stations.

This presents the fundamental challenge but also, Dowdy says, a key opportunity: “There’s a potential for them to be better integrated into towns and cities if they sit with other businesses that can use some of their exhaled heat and energy. A scheme by architecture firm Scott Brownrigg imagines a datacentre as being just one or two floors of a mixed-use building with, perhaps, urban farming that could use the heat that they give off. And in Scandinavia, some data centres are diverting their excess heat is poured into the district’s heating network.”

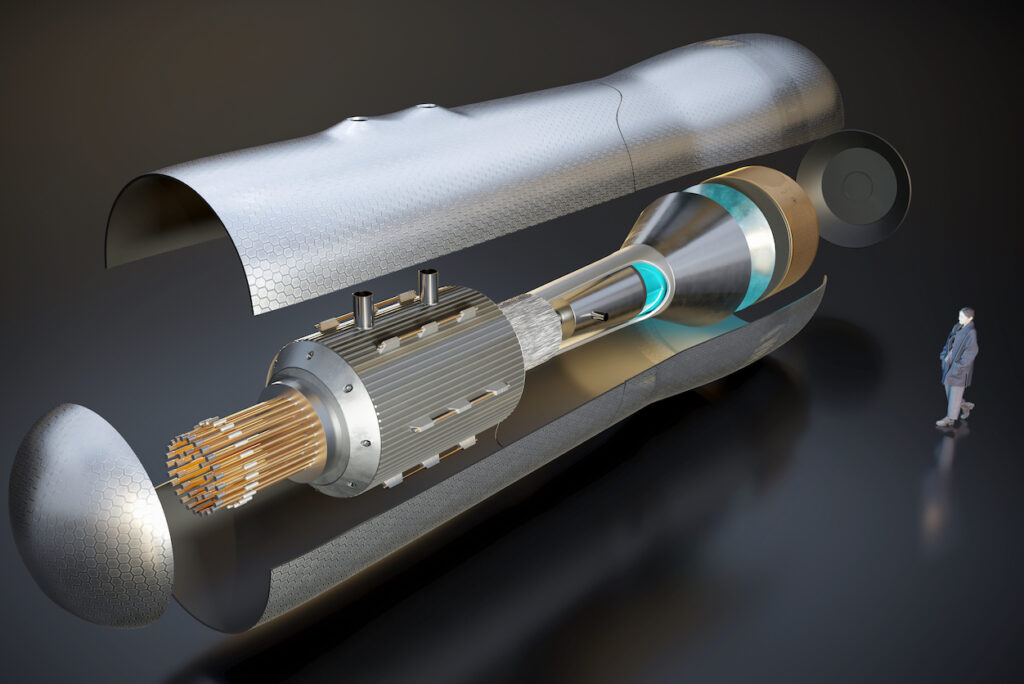

Some designers are going further still, and proposing nuclear batteries (NBs) – micro nuclear reactors that take up a fraction of the space of conventional generators, transforming the potential future design and zoning of data centres. MIT’s Advanced Nuclear & Production Experts Group, together with architect Iain Macdonald, have proposed a concept data centre in Barcelona based on the technology. “They could be become part of the structure – and then they don’t need to be built on that massive scale,” says Dowdy. “That’s going to have the potential to be the game changer.”

However society reaches an accommodation with these buildings, reach it we must, because our thirst for data is only going to keep growing. Just to choose one example – and there are many – Power House makes the point that “cars and roads could drive the next huge demand for data centres as smart cities connect autonomous vehicles to the Internet of Things – all accessing and creating vast amounts of data every second.”

Power House: the architecture of data centres, Roca Gallery London, ends on 14 April 2022